Call Us For Easy

Confidential Assistance

503-506-0101

It only takes 5 minutes to get started

Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS): The Physical Reality of Chronic Marijuana Use

Posted on: January 1st, 2026 by writer

Table of Contents

- Understanding the Paradox: How Cannabis Can Cause What It’s Meant to Cure

- The Escalating Stages: How CHS Progresses from Morning Nausea to Hospitalization

- High-THC Products and the Rising Tide of CHS Cases

- Why Do Hot Showers Help? The TRPV1 Receptor Connection

- Beyond Discomfort: When CHS Becomes a Medical Emergency

- The Diagnostic Challenge: Distinguishing CHS from Other Vomiting Disorders

- The Only Cure for CHS: Complete Cannabis Cessation (And Why That’s Harder Than It Sounds)

- Key Takeaways

For many people, cannabis is seen as a harmless way to relax, manage pain, or even treat nausea. But what happens when the drug meant to calm your stomach starts causing severe, uncontrollable vomiting instead?

Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS) is a little-known but increasingly common condition affecting long-term marijuana users—particularly those consuming high-potency products like concentrates and vapes. Despite cannabis being widely prescribed as an anti-nausea medication, chronic use can trigger a dangerous paradox: severe, cyclical vomiting that only worsens with continued use.

In Oregon, where recreational cannabis has been legal since 2015 and high-THC products dominate the market, emergency departments are seeing a dramatic rise in CHS cases. Many patients spend hours in scalding hot showers trying to find relief, unaware that their marijuana habit is the root cause.

This article explores the science behind CHS, why it’s becoming more prevalent, and why residential treatment programs like Pacific Ridge are uniquely positioned to help patients break the cycle of chronic cannabis use before it leads to life-threatening complications.

Understanding the Paradox: How Cannabis Can Cause What It’s Meant to Cure

CHS represents a medical paradox where the same compound used to treat nausea—THC—becomes the cause of severe, recurring vomiting episodes when used chronically at high doses.

The Endocannabinoid System (ECS): At low doses, THC interacts with CB1 receptors in the brain to suppress nausea and vomiting. This is why cannabis is prescribed for chemotherapy patients. The body’s endocannabinoid system plays a vital role in regulating homeostasis, including gastrointestinal motility and nausea control.

The Biphasic Effect: With chronic, high-dose use, CB1 receptors in the gut become desensitized or dysregulated, leading to gastroparesis (delayed stomach emptying) and severe vomiting. What works as medicine in small doses becomes poison in sustained, high quantities.

Why It’s Misunderstood: Patients often don’t connect their symptoms to cannabis use. Many increase consumption, believing it will help—creating a dangerous feedback loop. This “learned behavior” stems from the initial relief cannabis provided, making it counterintuitive that the same substance now causes their distress.

The “Scromiting” Phenomenon: Emergency medicine professionals coined the term “scromiting” (screaming and vomiting) to describe the intense abdominal pain and violent retching episodes characteristic of CHS. The combination of debilitating pain and uncontrollable vomiting creates a medical emergency that often leaves patients and physicians baffled.

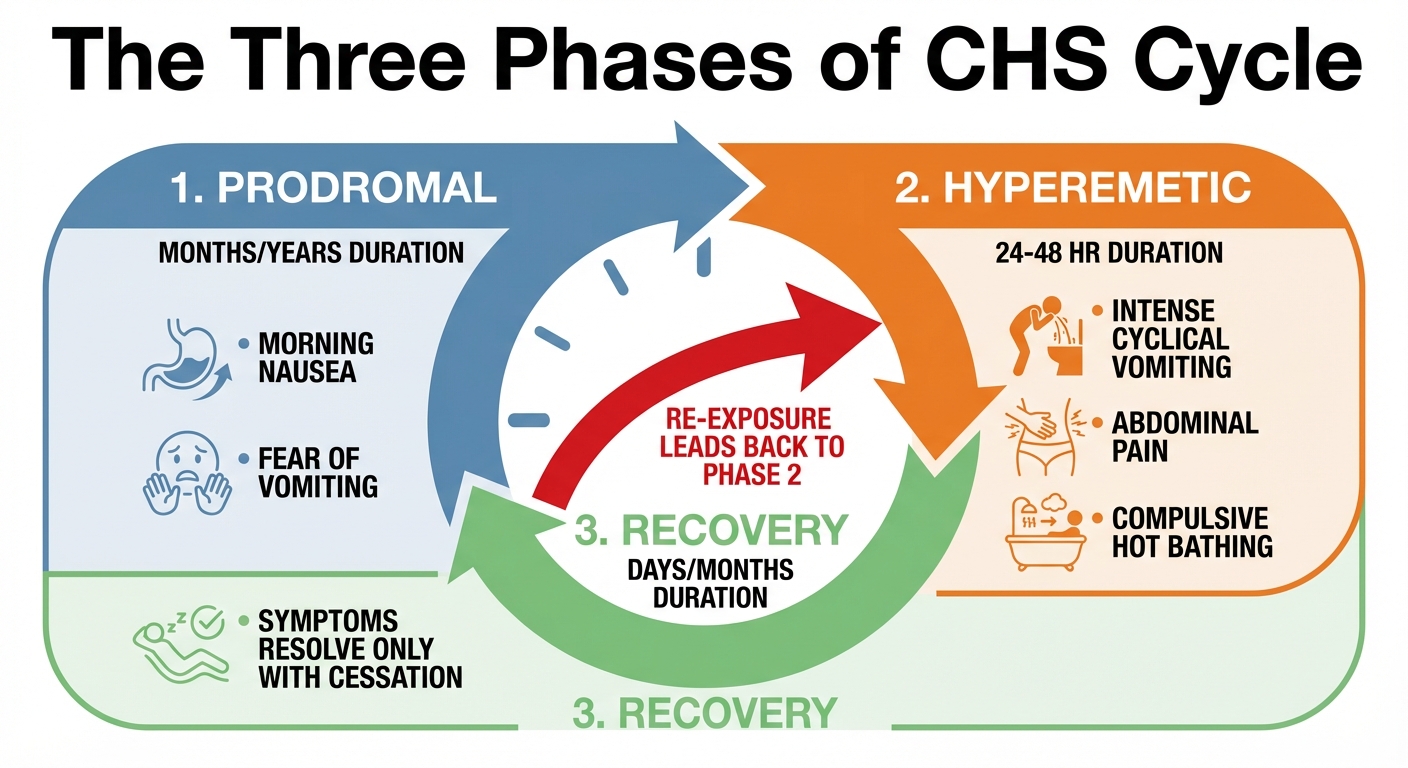

The Escalating Stages: How CHS Progresses from Morning Nausea to Hospitalization

CHS doesn’t appear overnight. It develops in three distinct phases, often over months or years, with symptoms escalating if cannabis use continues.

Phase 1: Prodromal (Early Warning Signs)

Duration: Months to years

During this initial phase, patients experience morning nausea, abdominal discomfort, and fear of vomiting. The symptoms are mild enough that most people continue their daily routines, and crucially, they maintain or increase cannabis use, believing it helps manage the nausea. Eating patterns remain relatively normal during this phase, making it easy to dismiss the symptoms as unrelated to cannabis consumption.

Phase 2: Hyperemetic (Acute Crisis)

Duration: 24-48 hours (can persist with continued use)

This phase marks the acute medical emergency. Patients experience intense, uncontrollable vomiting known as “paroxysms”—sudden, violent episodes that occur without warning. Severe abdominal pain accompanies the vomiting, along with rapid dehydration and potentially dangerous weight loss.

The “Hot Shower Test”: Patients compulsively take scalding showers or baths for temporary relief—a pathognomonic (uniquely characteristic) sign of CHS. This behavior, termed “hydrophilia” in medical literature, involves spending hours per day in hot water seeking relief. Some patients report taking 10 or more showers daily, often at temperatures hot enough to cause skin burns.

Phase 3: Recovery

Duration: Days to months

The recovery phase has one critical requirement: complete cessation of cannabis use. When use stops, symptoms resolve and normal eating patterns return. However, this phase comes with an important warning: re-exposure to cannabis almost always triggers immediate relapse of symptoms.

A Real Case:

A 23-year-old male with 5 years of daily cannabis use visited the ER six times over two years with severe vomiting and abdominal pain. He took up to 10 hot showers daily. After multiple expensive, invasive tests—CT scans, endoscopy, colonoscopy—all returned normal, he was misdiagnosed with viral gastroenteritis and anxiety. Only after specific questioning about cannabis use and hot shower habits was CHS diagnosed. Symptoms resolved within 48 hours of stopping use—but returned immediately when he relapsed three months later.

This case illustrates the diagnostic delay that plagues CHS recognition. Patients often undergo unnecessary testing because they don’t disclose cannabis use, or clinicians fail to ask the right questions.

High-THC Products and the Rising Tide of CHS Cases

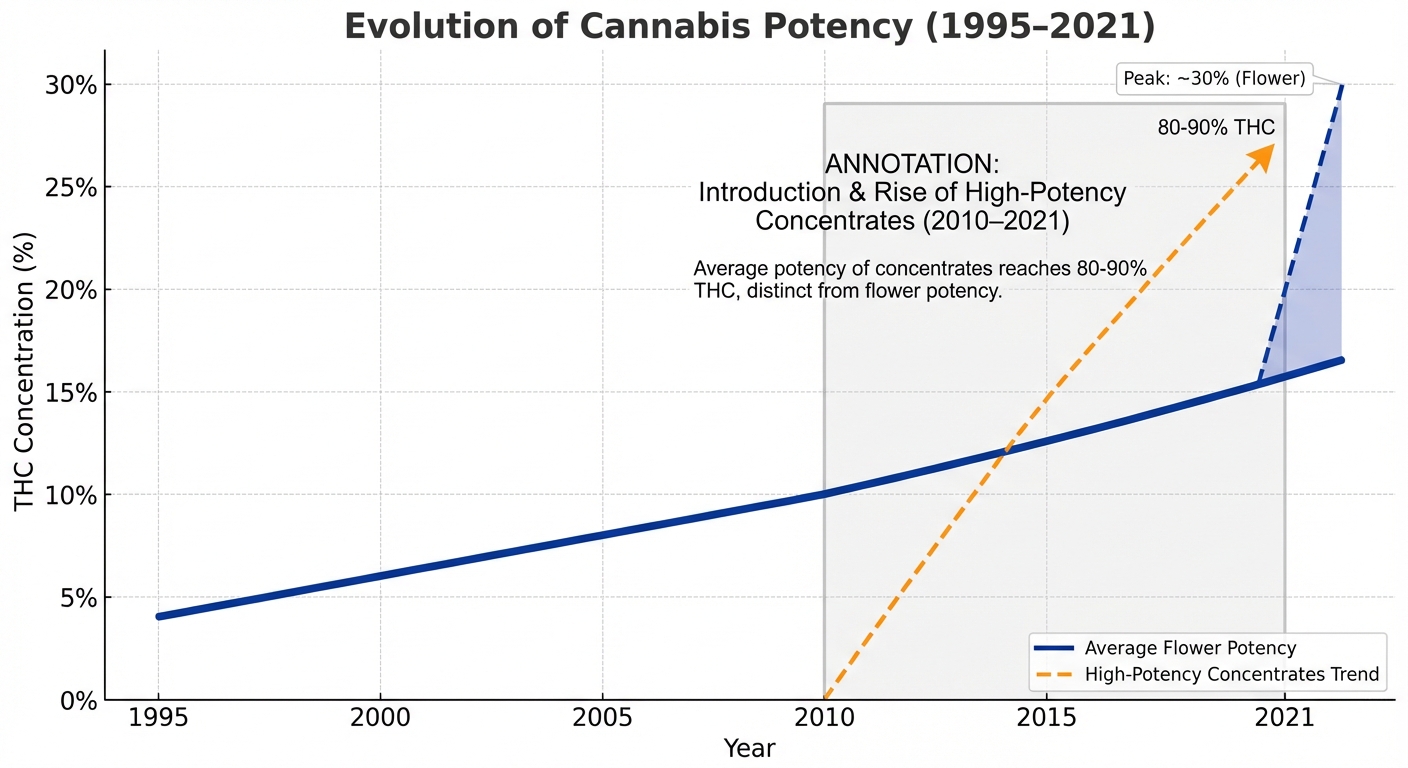

The dramatic increase in cannabis potency over the past 30 years—especially in legal markets like Oregon—is directly correlated with the surge in CHS cases.

Historical Potency Trends:

In 1995, average THC content in cannabis flower was approximately 4%. By 2010, that average had climbed to 10%, and concentrates entered the market with THC levels between 40-50%. Fast forward to 2021, and flower now averages 15-30% THC, while concentrates—including dabs, waxes, and vapes—regularly exceed 80-90% THC.

The Oregon Context:

Oregon’s mature recreational market prioritizes high-THC strains, with dispensaries competing on potency rather than quality or balance. Concentrates deliver massive boluses of THC, exceeding the body’s tolerance ceiling and rapidly pushing chronic users toward the biological tipping point where CHS develops. Research shows users of high-potency concentrates face significantly higher risk of developing CHS compared to occasional flower users.

Emergency Department Data:

Colorado, which legalized recreational cannabis before Oregon, provides a predictive model for what happens in mature legal markets. Studies show Colorado experienced a three-fold increase in cannabis-related vomiting ED visits after legalization. Even more striking, a survey of urban ER patients with frequent cannabis use found 32.9% met diagnostic criteria for CHS, suggesting the condition is vastly underdiagnosed.

Why Pacific Ridge Sees This: Oregon’s unrestricted access to high-potency products creates specific urgency for treatment centers equipped to address CHS-related complications. As the legal market matures and potency continues to climb, residential programs become essential for managing the physical consequences of chronic use.

Why Do Hot Showers Help? The TRPV1 Receptor Connection

One of CHS’s most distinctive features is the compulsive need for scalding hot showers. Understanding the science behind this behavior helps differentiate CHS from other vomiting disorders.

TRPV1 Receptors Explained:

TRPV1 (Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1) receptors normally signal heat and pain sensations. They also regulate gastric motility—the movement of the stomach that processes food. Chronic cannabis use downregulates these receptors, disrupting normal digestive function.

The Hot Water Mechanism:

Scalding water activates cutaneous (skin) TRPV1 receptors. This sensory input overrides nauseogenic (nausea-causing) signals from the gut to the brain, providing temporary relief—but only while in the hot water. Once the patient leaves the shower, symptoms return, often with increased intensity.

Clinical Implications:

Patients report spending hours per day in hot water, a behavior so specific to CHS that it’s considered a diagnostic criterion. This “hydrophilia” leads to secondary complications including:

- Dehydration (ironically worsening the condition)

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Cutaneous burns from scalding temperatures

- Some patients develop second-degree burns from water temperatures exceeding 120°F (49°C)

Alternative Treatment: Topical capsaicin cream—the compound that makes chili peppers hot—applied to the abdomen can activate TRPV1 receptors without the burn risk. Emergency departments increasingly use capsaicin cream as a safer alternative to hot water therapy during acute CHS episodes.

Beyond Discomfort: When CHS Becomes a Medical Emergency

While CHS is often dismissed as “just vomiting,” the condition can lead to severe, life-threatening physical complications requiring immediate medical intervention.

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI):

Profuse vomiting causes severe dehydration, which can rapidly progress to acute kidney injury. A systematic review found AKI is a frequent CHS complication, often requiring aggressive IV fluid resuscitation. Without prompt treatment, kidney damage can become permanent.

Mallory-Weiss Tears:

Violent retching can tear the esophageal lining, leading to hematemesis—vomiting blood. These tears constitute a medical emergency requiring immediate intervention to prevent life-threatening hemorrhage.

Electrolyte Derangement:

Loss of potassium and sodium through vomiting disrupts the body’s electrical balance. This can trigger cardiac arrhythmias (irregular heartbeat) and severe muscle spasms. Electrolyte imbalances require careful medical monitoring and IV electrolyte replacement to prevent cardiac complications.

Weight Loss and Malnutrition:

Chronic inability to keep food down leads to dangerous weight loss and long-term nutritional deficiencies. Some CHS patients lose 20-30 pounds during severe episodes, with nutritional consequences that persist even after symptoms resolve.

Why Residential Treatment Matters:

These complications require the level of medical oversight available in residential settings like Pacific Ridge—not just outpatient therapy. Round-the-clock medical monitoring, IV fluid administration, and supervised nutrition support become essential for managing acute CHS while addressing the underlying Cannabis Use Disorder.

The Diagnostic Challenge: Distinguishing CHS from Other Vomiting Disorders

CHS is frequently misdiagnosed as Cyclical Vomiting Syndrome (CVS), gastroenteritis, or anxiety, leading to unnecessary testing, delayed treatment, and continued suffering.

CHS vs. CVS: Key Differences

| Characteristic | CHS | CVS |

|---|---|---|

| Cause | Chronic cannabis use | Idiopathic or migraine-related |

| Hot Shower Relief | Highly specific diagnostic sign | Rarely seen |

| Treatment | Complete cannabis cessation | Varies; anti-migraine medications may help |

| Resolution | 48 hours to 1 week after stopping cannabis | Variable; may require ongoing management |

Why Diagnosis Is Delayed:

- Patients don’t volunteer cannabis use history due to stigma, privacy concerns, or genuine belief that their use is unrelated to symptoms

- Clinicians fail to ask about cannabis consumption or hot bathing behavior, focusing instead on more common causes of vomiting

- Standard anti-nausea medications like Zofran (ondansetron) don’t work for CHS because the mechanism involves the endocannabinoid system, not the serotonin pathways these drugs target

The Diagnostic Process:

Proper CHS diagnosis requires:

- Detailed cannabis use history including frequency, potency, and method of consumption

- Specific questioning about hot shower or bath behavior—most patients won’t volunteer this information unless prompted

- The Rome IV criteria provide a standardized diagnostic framework

- Appropriate testing to exclude other GI disorders

The Cost of Misdiagnosis:

Delayed diagnosis leads to unnecessary CT scans, endoscopies, and colonoscopies—invasive procedures that cost thousands of dollars and expose patients to risk without identifying the problem. Meanwhile, symptoms continue with ongoing cannabis use, and healthcare costs mount while patients suffer needlessly.

The Only Cure for CHS: Complete Cannabis Cessation (And Why That’s Harder Than It Sounds)

While the medical consensus is clear—CHS only resolves with complete cessation of cannabis use—the reality of achieving and maintaining abstinence is complicated by addiction physiology.

Medical Interventions for Acute Episodes:

Haloperidol: Unlike standard antiemetics, haloperidol (an antipsychotic) shows high efficacy in stopping CHS vomiting in the ER. It works by interacting with dopamine receptors in the brain’s chemoreceptor trigger zone—a different mechanism than traditional anti-nausea medications.

Capsaicin Cream: Topical application to the abdomen activates TRPV1 receptors, providing relief without scalding water. Emergency departments increasingly stock capsaicin cream specifically for CHS treatment.

IV Fluids and Electrolytes: Critical for treating dehydration and electrolyte imbalances that can trigger cardiac complications. Aggressive fluid resuscitation often requires hospital admission during acute episodes.

The Permanent Solution: Complete Cannabis Abstinence

Symptoms typically resolve within 48 hours to one week of stopping use. However, any re-exposure to cannabis triggers immediate symptom recurrence—there is no “safe” amount of cannabis for someone with CHS history.

Why Quitting Is Complicated:

Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD): Patients with CHS typically meet DSM-5 criteria for CUD—they’re physically and psychologically dependent on cannabis. The idea of simply “stopping” ignores the reality of addiction.

Withdrawal Symptoms: Cessation triggers irritability, anxiety, insomnia, and decreased appetite—symptoms the patient previously self-medicated with cannabis. Without professional support, these withdrawal symptoms often drive relapse.

The Relapse Cycle: Without structured treatment, patients often relapse to treat withdrawal symptoms, immediately re-triggering CHS. This creates a vicious cycle where physical illness and addiction reinforce each other.

Why Residential Treatment (Pacific Ridge) Is Necessary:

- Medical Oversight: Management of dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, and acute symptoms during early cessation requires professional medical monitoring unavailable in outpatient settings

- Supervised Detox: Professional support through withdrawal in an environment without access to cannabis breaks the immediate relapse pattern that perpetuates CHS

- Therapeutic Support: Evidence-based addiction treatment addressing underlying CUD—not just the physical symptoms—provides the foundation for long-term recovery

- Breaking the Cycle: A controlled environment prevents the immediate relapse that would re-trigger CHS, giving patients time to develop coping strategies for managing withdrawal and triggers

The American Society of Addiction Medicine emphasizes that CHS patients require comprehensive addiction treatment, not just medical management of acute symptoms. Treating the vomiting without addressing the Cannabis Use Disorder virtually guarantees relapse.

Key Takeaways

Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome is no longer a rare medical curiosity—it’s an emerging public health concern in states with legal, high-potency cannabis markets. For long-term marijuana users, particularly those consuming concentrates and high-THC products, CHS represents a real and potentially life-threatening consequence.

The paradox of CHS—where the drug used to treat nausea becomes its cause—highlights the complex relationship between cannabis and the body’s regulatory systems. While cannabis remains a valuable medical tool for some patients, chronic high-dose use can trigger severe physiological dysfunction that only resolves with complete abstinence.

For patients suffering from CHS, the path to recovery requires more than just stopping cannabis use. It requires addressing the underlying Cannabis Use Disorder through comprehensive residential treatment—medical oversight to manage acute complications, supervised detox to navigate withdrawal, and evidence-based therapy to prevent relapse.

If you or someone you know is experiencing severe, cyclical vomiting combined with chronic cannabis use and compulsive hot bathing, it’s time to seek professional help. Pacific Ridge offers the medical expertise and therapeutic support necessary to break the cycle of CHS and achieve lasting recovery.

Take the First Step Toward Recovery

Don’t let Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome control your life. Pacific Ridge’s residential treatment program can help you or a loved one recover from CHS and Cannabis Use Disorder.

References:

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). (2011). Regulation of nausea and vomiting by cannabinoids

- Cleveland Clinic. (2023). Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome

- National Library of Medicine. (2022). Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review

- Cedars-Sinai. (2022). Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome Phases

- Temple Health. (2024). Why Do Hot Showers Help CHS?

- Mayo Clinic. (2023). Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome Diagnosis and Treatment

- Journal of Investigative Medicine High Impact Case Reports. (2017). Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Case Report of a Paradoxical Reaction

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2022). Cannabis (Marijuana) Potency

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2021). Concentrate use and CHS risk factors

- JAMA Network Open. (2021). Association of Cannabis Legalization With Emergency Department Visits for Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome

- Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. (2018). Prevalence of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome Among Regular Marijuana Smokers in an Urban Emergency Department

- Cedars-Sinai. (2019). CHS vs CVS: Knowing the Difference

- American Journal of Kidney Diseases. (2016). Acute Kidney Injury Associated With Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome

- Academic Emergency Medicine. (2018). Haloperidol versus Ondansetron for Treatment of Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome

- British Journal of General Practice. (2019). Topical capsaicin for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome

- American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM). (2023). Marijuana and Cannabinoids: A Review of Clinical Issues

Posted in Treatment

Recent Posts

- From Pills to Fentanyl: Understanding the Progression of Opioid Addiction

- Sober Activities in the Willamette Valley: Rediscovering Life Without Substances

- Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS): The Physical Reality of Chronic Marijuana Use

- Protecting Your Career While Seeking Treatment: FMLA and Privacy Rights for Oregon Employees

Are you looking for help?

Pacific Ridge is a residential drug and alcohol treatment facility about an hour from Portland, Oregon, on the outskirts of Salem. We’re here to help individuals and families begin the road to recovery from addiction. Our clients receive quality care without paying the high price of a hospital. Most of our clients come from Oregon and Washington, with many coming from other states as well.

Pacific Ridge is a private alcohol and drug rehab. To be a part of our treatment program, the client must voluntarily agree to cooperate with treatment. Most intakes can be scheduled within 24-48 hours.

Pacific Ridge is a State-licensed detox and residential treatment program for both alcohol and drugs. We provide individualized treatment options, work closely with managed care organizations, and maintain contracts with most insurance companies.

Quick links

Recent Posts

- From Pills to Fentanyl: Understanding the Progression of Opioid Addiction

- Sober Activities in the Willamette Valley: Rediscovering Life Without Substances

- Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS): The Physical Reality of Chronic Marijuana Use

- Meth-Induced Psychosis: Understanding the Brain’s Recovery Timeline

Contact Us

Pacific Ridge- 1587 Pacific Ridge Ln SE

Jefferson, OR 97352 - Email:

[email protected] - Phone:

503-506-0101 - Fax:

503-581-8292

- Copyright © 2026 Pacific Ridge - All Rights Reserved. Web Design & SEO by Lithium

- Follow us on