Call Us For Easy

Confidential Assistance

503-506-0101

It only takes 5 minutes to get started

Meth-Induced Psychosis: Understanding the Brain’s Recovery Timeline

Posted on: January 1st, 2026 by writer

Table of Contents

- The P2P Shift: Why Today’s Meth Causes Faster, More Severe Psychosis

- Inside the Brain: How Meth Triggers Schizophrenia-Like Psychosis

- Month by Month: The Brain’s Healing Journey from Psychosis to Clarity

- From “Holes in the Brain” to Neuroplasticity: How Science Changed the Story

- Creating a Low-Stress Environment: The Family’s Role in Neuroplasticity

- Methamphetamine in the Pacific Northwest: Why Pacific Ridge’s Expertise is Critical

- Key Takeaways

For families watching a loved one struggle with methamphetamine addiction, few symptoms provoke more terror than psychosis. The sudden paranoia, the conversations with people who aren’t there, the frantic accusations—it’s as if the person you know has been replaced by a stranger. In a single moment, your husband, daughter, or best friend transforms into someone unrecognizable, convinced that unseen enemies are plotting against them or that invisible insects are crawling beneath their skin. Here in Oregon, where Pacific Ridge serves communities grappling with one of the nation’s most severe methamphetamine crises, these scenes play out with heartbreaking frequency. But amid the chaos and fear, there’s a truth that families desperately need to hear: the terrifying symptoms of meth-induced psychosis are not permanent. With proper treatment and time, the brain demonstrates a remarkable capacity to heal itself. Landmark research published in the Journal of Neuroscience tracked methamphetamine users through 14 months of abstinence, using PET scans to document something extraordinary—the brain’s dopamine transporters, devastated by chronic meth use, recovered to near-normal levels. This wasn’t speculation or hopeful thinking. It was visible, measurable proof that the brain can rebuild itself. This article will walk you through the neuroscience of methamphetamine-associated psychosis, provide a month-by-month timeline of what recovery actually looks like, and offer families practical, research-backed guidance for supporting their loved ones through the healing process. Understanding the science doesn’t make the journey easier, but it does make it bearable—because you’ll know that the person you love is still in there, and their brain is working to find its way back.

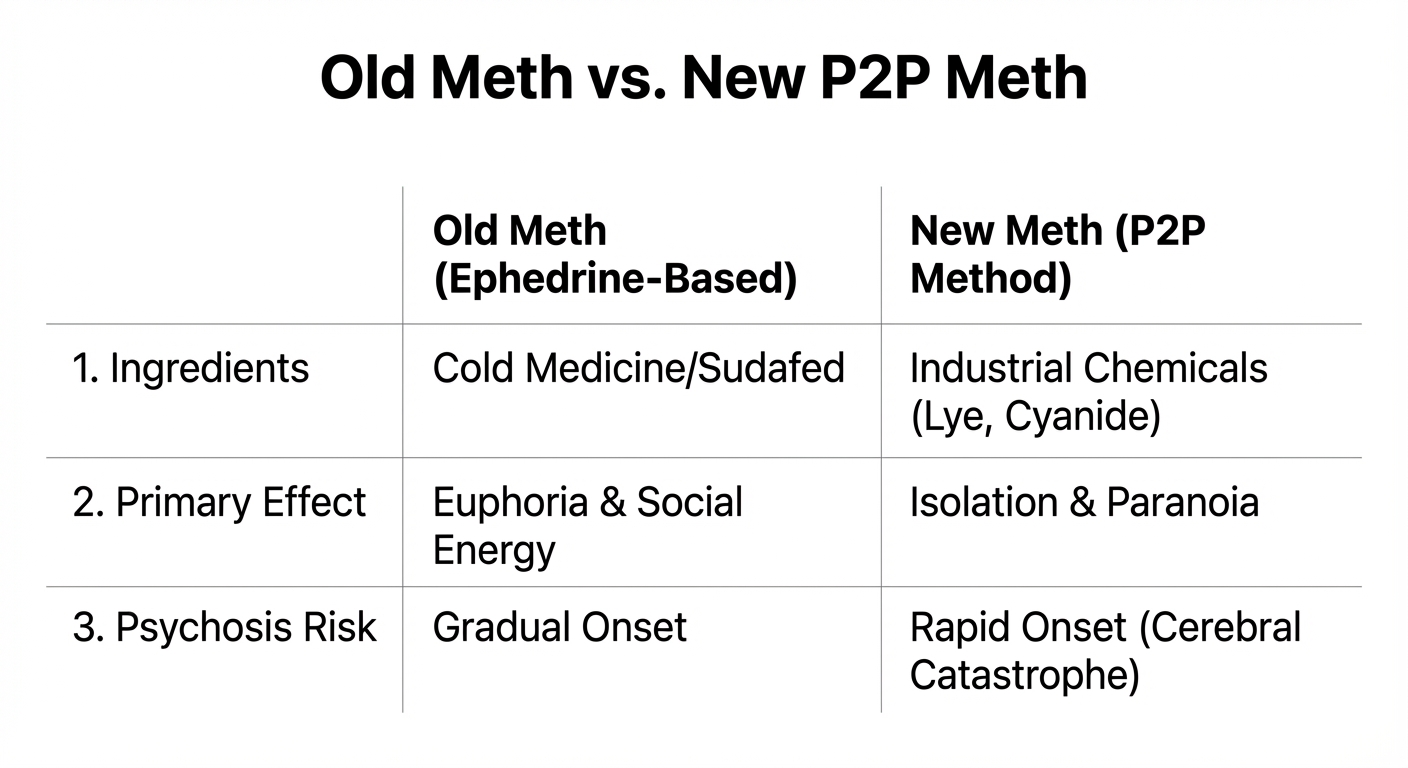

The P2P Shift: Why Today’s Meth Causes Faster, More Severe Psychosis

To understand why methamphetamine-induced psychosis has become so prevalent and severe, you need to understand a fundamental change in how the drug itself is made. The methamphetamine that circulated in the early 2000s—the drug depicted in shows like Breaking Bad—was chemically different from what’s on the streets today. Historically, methamphetamine was synthesized from ephedrine, a compound derived from cold medicines. This “old meth” produced a distinctive high: intensely social, euphoric, and energizing. Users would talk compulsively, engage in marathon sexual encounters, and work on projects for days without sleep. The drug was destructive, but its effects were somewhat predictable. Everything changed with the shift to P2P methamphetamine, named after the precursor chemical phenyl-2-propanone. When authorities cracked down on ephedrine access, Mexican cartels and domestic producers pivoted to this alternative synthesis method, which relies on harsh industrial chemicals including cyanide and lye. The result is a chemically distinct substance that produces profoundly different effects on the brain.

Users of P2P methamphetamine report bypassing the euphoric, social phase entirely. Instead, they experience immediate isolation, overwhelming paranoia, and vivid hallucinations. Journalist Sam Quinones, who investigated this transformation extensively, described the phenomenon as a “cerebral catastrophe”—a fitting term for the wave of severe mental illness that followed the drug supply change. The statistics tell a sobering story. Research indicates that approximately 40% of regular methamphetamine users now experience psychotic symptoms, compared to significantly lower rates in previous decades. This isn’t because people are using more of the drug—though many do—but because the drug itself has become fundamentally more neurotoxic. For treatment centers like Pacific Ridge, this evolution demands a different clinical approach. The detox period must be longer. The psychiatric support must be more intensive. The expectation that someone will “snap out of it” after a few days of sleep is dangerously outdated. Today’s methamphetamine doesn’t just disrupt the brain temporarily—it wreaks havoc on neural systems in ways that require months of careful, supervised recovery.

Inside the Brain: How Meth Triggers Schizophrenia-Like Psychosis

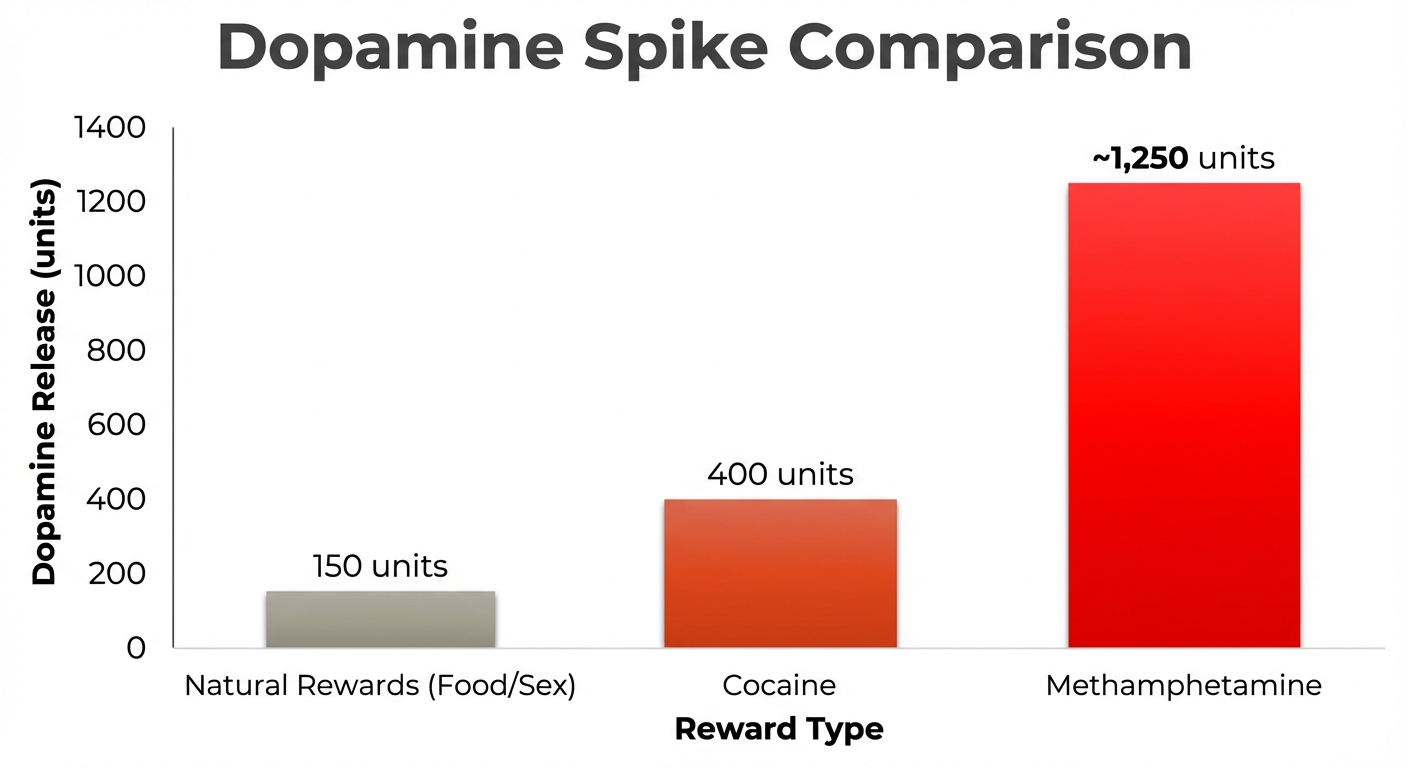

To understand why methamphetamine produces such severe psychotic symptoms, you need to understand what the drug does to your brain’s reward system at a molecular level. The mechanism is both elegant and catastrophic. Every pleasurable experience—eating a good meal, having sex, achieving a goal—triggers the release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter that signals “this is important, remember this, do it again.” A delicious dinner might increase your dopamine levels by 100-200 units above baseline. That’s enough to make you feel satisfied and motivated to seek out that restaurant again. Methamphetamine doesn’t just nudge your dopamine levels up. It detonates them. A single dose can spike dopamine concentrations to 1,250 units—more than twelve times the natural response to life’s most intense pleasures.

This flood of dopamine overwhelms the mesolimbic pathway, the brain’s primary reward circuit. Normally, this system helps you identify what matters—a potential threat, a romantic opportunity, a source of food. When dopamine surges to extreme levels, the system malfunctions, assigning profound significance to meaningless stimuli. The shadow in the corner becomes an intruder. The car that happened to turn down your street three times is surveillance. The barely audible mumbling from the next apartment is people plotting against you. This phenomenon—called aberrant salience—explains why methamphetamine psychosis so closely resembles paranoid schizophrenia. Both conditions involve dysregulated dopamine signaling in the same brain regions, producing nearly identical symptom clusters: auditory hallucinations, persecution delusions, and tactile hallucinations like formication (the sensation of insects crawling under your skin, which users often describe as “meth mites”). But here’s the critical distinction that families need to understand: there are two types of methamphetamine-associated psychosis, and they have very different timelines. Acute psychosis occurs during active intoxication or in the immediate days following use. It typically resolves within one week of abstinence as the drug clears the system and dopamine levels begin normalizing. This is the psychosis that dissipates with sleep, nutrition, and safety. Persistent psychosis is far more challenging. Studies suggest that up to 30% of methamphetamine users experience psychotic symptoms that continue for months or even years after their last use. These individuals require long-term psychiatric care alongside addiction treatment because their brains have sustained deeper damage to the dopamine system. The good news—and this is what the rest of this article will explore—is that even persistent psychosis can improve dramatically with time and proper treatment. The brain’s capacity for repair, given the right conditions, is far greater than most people realize.

Month by Month: The Brain’s Healing Journey from Psychosis to Clarity

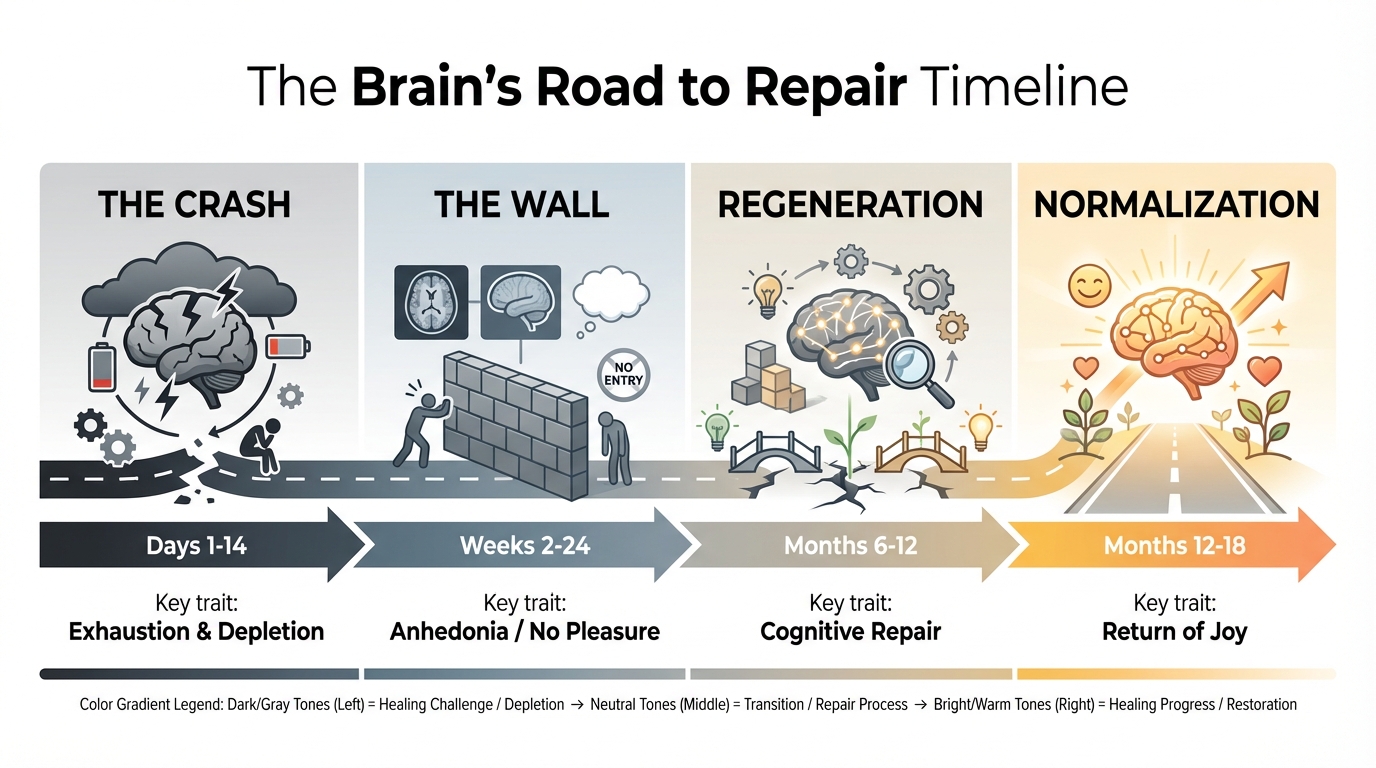

Recovery from methamphetamine-induced psychosis doesn’t follow a smooth, predictable trajectory. Instead, it unfolds in distinct phases, each with its own challenges and milestones. Understanding this timeline helps families set realistic expectations and recognize progress when it’s happening—even when it doesn’t feel like enough.

Phase 1: The Crash (Days 1–14)

The first two weeks after methamphetamine cessation are defined by a single word: depletion. After months or years of artificially flooding the brain with dopamine, the system is utterly exhausted. There’s simply nothing left in the tank. During this phase, your loved one will likely sleep 12-16 hours a day. This isn’t laziness—it’s biology. The brain is attempting to restore its baseline neurochemistry through the only mechanism available: rest. Appetite returns with startling intensity. People who barely ate during active use suddenly consume enormous quantities of food as their body tries to repair the damage. Psychologically, this period is brutal. The acute psychotic symptoms—the vivid hallucinations, the intense paranoia—typically begin fading by days 7-10. But they’re replaced by crushing depression and anxiety. Without artificial dopamine stimulation, nothing feels good. Nothing feels like anything. There’s another critical process happening during this phase: REM rebound. Chronic methamphetamine use devastates normal sleep architecture, particularly REM sleep—the stage associated with emotional processing and memory consolidation. During the crash phase, the brain attempts to compensate by dramatically increasing REM sleep duration. This flood of intense dreams and nightmares can be disorienting, but it’s actually a sign of healing. The acute paranoia might still flare during this window, particularly in response to stress or unexpected stimuli. The brain’s threat-detection systems remain hypersensitive, requiring a calm, predictable environment to begin recalibrating.

Phase 2: The Wall (Weeks 2–24)

If the crash phase is about depletion, the wall phase is about absence. This is the period that breaks people—the stretch of months when life feels colorless, pointless, and overwhelmingly difficult despite being clean. The defining feature of this phase is anhedonia—the complete inability to experience pleasure. Activities that used to bring joy—music, food, sex, hobbies—register as neutral or unpleasant. The brain’s reward system, having downregulated its dopamine receptors to survive the meth-induced floods, now struggles to respond to normal stimuli. Cognitive deficits become painfully apparent during this window. Memory problems, difficulty concentrating, impaired decision-making—all reflect the ongoing dysfunction in the prefrontal cortex and striatum. Your loved one might forget appointments, struggle to follow conversations, or make choices that seem inexplicably poor. This is the phase where relapse risk peaks, and the reason is straightforward: from the user’s perspective, sobriety isn’t working. They’re not high, but they’re also not experiencing any of the benefits they were promised. Life is just gray, difficult, and exhausting. PET scan research provides crucial insight into what’s happening beneath the surface during this period. At one month of abstinence, dopamine transporter levels in the striatum—essentially, the machinery that delivers dopamine where it needs to go—remain significantly depleted compared to healthy individuals. The brain is working to rebuild these systems, but the process is painstakingly slow. This is why residential treatment during this phase is so valuable. When the internal experience is one of persistent emptiness, external structure, support, and medical oversight become essential. Pacific Ridge and similar facilities provide the scaffolding that keeps people stable during the months when their own motivation system isn’t yet functional.

Phase 3: Visible Regeneration (Months 6–14)

Somewhere around the six-month mark, something shifts. It’s rarely dramatic—more like waking up one morning and realizing that you felt something resembling normal the day before. Maybe a meal actually tasted good. Maybe a conversation was genuinely interesting rather than something to endure. This is the phase where neuroscience transforms from abstract theory into lived experience. The brain is actively generating new neurons in the prefrontal cortex, a process called neurogenesis. The dopamine transporters that were damaged during active use are being repaired and replaced. Receptor sensitivity is normalizing. The landmark study that gives families the most concrete hope tracked this regeneration process using PET scans at various intervals. The results were extraordinary: after 14 months of sustained abstinence, dopamine transporter levels in the striatum had recovered to near-normal levels. Not perfectly normal—there was still some measurable deficit—but functionally normal. What does this look like in daily life? People report that colors seem brighter. Music sounds better. Jokes are actually funny again. The capacity for spontaneous joy—laughing at something unexpected, feeling genuinely excited about a plan—begins returning. Decision-making improves. The fog lifts. Memory consolidates. Emotional regulation becomes easier. The hair-trigger anger and crushing sadness that characterized the earlier phases start fading into something more manageable. This is when families start saying, “I’m getting glimpses of who they used to be.” The 14-month milestone doesn’t represent complete recovery—some deficits may persist for years, and certain individuals may never fully return to baseline. But it represents the threshold where the brain has regained enough function that continued healing becomes self-sustaining. The person can now engage meaningfully in therapy, maintain employment, rebuild relationships, and develop the skills necessary for long-term sobriety.

From “Holes in the Brain” to Neuroplasticity: How Science Changed the Story

If you were a teenager in the early 2000s, you probably saw the anti-drug advertisements: brain scans showing dark voids where brain tissue should be, accompanied by dire warnings about “holes in your brain” from methamphetamine use. The imagery was visceral and terrifying—and deeply misleading. Those campaigns were based on a fundamental misunderstanding of what brain imaging actually shows. The dark areas in PET scans don’t represent missing brain tissue—they show reduced metabolic activity in specific regions. The brain cells are still there; they’re just not functioning properly. This distinction might seem semantic, but it’s the difference between permanent structural damage and reversible functional impairment. The “holes in the brain” narrative created a generation of recovering addicts who believed they were fundamentally, irreversibly broken. If you’re told your brain is permanently damaged, why bother trying to stay sober? The damage is done. Modern neuroscience tells a radically different story, one centered on a concept called neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections throughout life. This isn’t wishful thinking or motivational speaking; it’s documented biological fact. The brain is not a static organ locked into place by early adulthood. It’s dynamic, adaptive, and remarkably resilient given the right conditions. A 2018 study examining risk factors for methamphetamine-associated psychosis demonstrated that cognitive behavioral therapy, combined with sustained abstinence, could reverse structural deficits in the parietal cortex—a region critical for spatial awareness and attention. These weren’t minor improvements; they were measurable changes in brain structure and function. This research fundamentally reframes what recovery means. Instead of “managing permanent damage,” we’re talking about “facilitating regeneration.” The brain wants to heal itself; the job of treatment is to create the conditions that allow that healing to occur. What are those conditions? Sleep normalization, proper nutrition, stress reduction, cognitive engagement, and most importantly, time free from further drug exposure. Every day of sobriety is a day the brain uses to rebuild. Every week, the repairs compound. Every month, function returns. This is where Pacific Ridge’s approach becomes particularly relevant. The treatment center isn’t just providing a safe place to detox—it’s creating a neuroplasticity accelerator. Structured sleep schedules. Nutrient-dense meals. Therapy that engages the prefrontal cortex. Physical activity that promotes BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), the protein that supports neuron growth. All of these interventions work synergistically to speed the brain’s natural healing process. The contrast with the old model couldn’t be starker. Where previous generations were told they’d destroyed their brains beyond repair, today’s recovering users can point to PET scans showing regeneration, to cognitive tests demonstrating improvement, to the lived experience of gradually reclaiming their mental clarity. Hope isn’t just an emotional state—it’s a neurobiological reality.

Creating a Low-Stress Environment: The Family’s Role in Neuroplasticity

While professional treatment provides the clinical framework for recovery, the home environment plays an equally crucial role in determining whether the brain can heal effectively. This might be frustrating news for families who feel they’ve already given everything they have, but it’s also empowering: there are specific, research-backed actions you can take to support your loved one’s neurobiological recovery. The most important concept to understand is Low Expressed Emotion, or LEE. This clinical term describes an environment characterized by calm communication, appropriate emotional boundaries, and minimal conflict. Research in psychiatric recovery—particularly for conditions like schizophrenia that share dopamine dysregulation with meth-induced psychosis—demonstrates that LEE environments significantly improve patient outcomes. Here’s why this matters at a neurochemical level: stress triggers dopamine release. For a brain that’s trying to downregulate its dopamine system back to normal sensitivity, chronic stress exposure essentially mimics the effects of drug use. High-conflict households, constant criticism, emotional over-involvement—all of these create a dopamine environment that delays recovery and increases relapse risk. This doesn’t mean you can’t set boundaries or that you should tolerate unacceptable behavior. It means that enforcement should be consistent, calm, and non-reactive. “You cannot stay here if you continue using” delivered evenly is protective. The same boundary delivered amid yelling and tears is neurochemically disruptive.

Practically, LEE looks like:

- Predictable daily routines (consistent meal times, sleep schedules, activities)

- Clear, written expectations rather than repeated verbal reminders

- Separation of the person from their behavior (“I love you, and this behavior isn’t acceptable” rather than “You’re destroying this family”)

- Designated quiet spaces where your loved one can retreat when overwhelmed

- Family members managing their own stress through therapy, support groups, and self-care

Nutrition provides another powerful lever for supporting brain recovery. Dopamine synthesis requires specific amino acids, vitamins, and minerals. A diet designed to support neurotransmitter production won’t cure addiction, but it will provide the raw materials the brain needs for repair.

The Brain-Healing Kitchen: Dopamine-Supporting Foods

- Turkey and chicken (high in tyrosine, the amino acid precursor to dopamine)

- Almonds and pumpkin seeds (magnesium supports neurotransmitter synthesis)

- Blueberries and strawberries (antioxidants reduce oxidative stress from past drug use)

- Leafy greens like spinach (folate supports methylation processes critical for neurotransmitter production)

- Fatty fish like salmon (omega-3s support neuroplasticity and reduce inflammation)

- Eggs (choline supports acetylcholine production, improving memory and cognition)

Avoid the temptation to turn this into a controlling health obsession. You’re not trying to “fix” your loved one through kale smoothies. You’re simply ensuring that when their brain reaches for the building blocks it needs to synthesize dopamine naturally, those resources are available. Sleep hygiene deserves special attention. Normalized sleep architecture—particularly restored REM sleep—is absolutely critical for emotional regulation and memory consolidation. Simple interventions make an enormous difference:

- Blackout curtains or sleep masks to eliminate light exposure

- Consistent bedtimes, even on weekends

- No screens 1-2 hours before bed (blue light suppresses melatonin)

- Cool room temperature (65-68°F is optimal for sleep)

- White noise machines to mask disruptive sounds

Finally—and this may be the most important point—maintain realistic expectations about progress. Recovery is not linear. There will be weeks where your loved one seems engaged, present, and hopeful, followed by weeks where they’re withdrawn, irritable, and depressed. This variability doesn’t mean treatment failed or that they’re using again. It means their brain is healing in fits and starts, with good neurochemical days and bad neurochemical days. The timeline research shows that significant improvement takes 6-14 months. That’s not 6-14 months until they’re “cured”—it’s 6-14 months until dopamine transporter function approaches normal. Celebrate the small victories: a morning where they woke up on their own, a conversation where they genuinely laughed, a day where they followed through on a plan. These moments are evidence of neurons rebuilding connections. You cannot control whether your loved one stays sober. But you can control whether your home becomes a place where their brain has the best possible chance to heal. That’s not a small thing—it might be the most important thing.

Methamphetamine in the Pacific Northwest: Why Pacific Ridge’s Expertise is Critical

The Pacific Northwest has long grappled with high rates of methamphetamine use, but recent years have seen this regional challenge escalate into a full-blown crisis. Understanding the specific dynamics of Oregon’s methamphetamine landscape helps clarify why facilities like Pacific Ridge aren’t just convenient options—they’re clinically necessary responses to a unique and evolving threat. Data from the Oregon Health Authority reveals a disturbing trend: unintentional drug overdose deaths involving methamphetamine surged dramatically between 2019 and 2021. This increase isn’t simply a matter of more people using the drug. It reflects the particular lethality of P2P methamphetamine combined with Oregon’s specific polysubstance use patterns. In Oregon, methamphetamine is increasingly contaminated with or deliberately mixed with fentanyl. This creates a uniquely dangerous pharmacological situation. Methamphetamine is a potent stimulant; fentanyl is an extremely potent depressant. When someone uses meth expecting stimulation and unknowingly ingests fentanyl, their body receives contradictory neurological signals. The result can be catastrophic—respiratory depression from the fentanyl occurring while the heart races from the methamphetamine, creating a cardiac crisis. From a treatment perspective, polysubstance use complicates every phase of recovery. Withdrawal symptoms become unpredictable and dangerous, requiring medical supervision rather than self-managed detox. Someone expecting to deal with meth crash symptoms—exhaustion, depression, hypersomnia—might instead experience the terrifying anxiety and physical agony of opioid withdrawal layered on top of stimulant depletion. This is why medical detox isn’t a luxury in Oregon—it’s a necessity. Attempting to withdraw from contaminated methamphetamine at home puts users at severe risk of complications including seizures, cardiac events, and unmanageable psychiatric symptoms that lead to relapse or worse. Pacific Ridge’s location near Salem positions the facility at the epicenter of these regional challenges. The treatment protocols aren’t generic addiction medicine—they’re specifically calibrated to the realities of Pacific Northwest methamphetamine use. That means:

- Extended detox timelines accounting for P2P meth’s longer psychiatric symptom duration

- Protocols for identifying and managing fentanyl exposure

- Cultural competency regarding the specific demographic groups most affected by Oregon’s meth crisis

- Integration with regional psychiatric services for persistent psychosis cases

- Ongoing adaptation to the evolving drug supply

Geographic proximity also matters for family involvement, which as we’ve discussed is critical for long-term recovery. A treatment center in Salem allows regular family therapy sessions, gradual home visits, and seamless transition to outpatient care without requiring cross-country travel. Recovery doesn’t end at discharge—it requires ongoing connection to local resources, support groups, and aftercare services. The regional expertise extends to understanding Oregon’s specific recovery infrastructure. Pacific Ridge staff know which local psychiatrists have experience with persistent meth-induced psychosis, which employers participate in recovery-friendly hiring programs, which housing resources exist for people transitioning out of residential treatment. This isn’t information you find online; it’s knowledge built through years of operating within the specific ecosystem of Oregon’s addiction treatment landscape. For families searching for care, this regional specialization should weigh heavily in the decision-making process. A facility that primarily treats opioid or alcohol addiction can provide excellent care for those conditions—but methamphetamine, particularly P2P methamphetamine, requires different clinical expertise. The psychiatric component is more complex. The timeline is longer. The risk of persistent symptoms is higher. Treatment providers need to understand what they’re dealing with, and that understanding comes from sustained experience with this specific population. Oregon’s methamphetamine crisis is not going away. The drug supply continues evolving, the formulations grow more dangerous, and the psychiatric consequences become more severe. In this environment, treatment centers with deep regional expertise aren’t just service providers—they’re essential infrastructure in a landscape where knowing what you’re dealing with can be the difference between recovery and relapse.

Key Takeaways

The journey from methamphetamine-induced psychosis to mental clarity is long, difficult, and punctuated by setbacks. But it is not impossible, and it is not permanent. The science is unequivocal: given time, proper treatment, and a supportive environment, the brain demonstrates remarkable healing capacity. The dopamine transporters that were decimated during active use regenerate over 12-14 months. The prefrontal cortex repairs itself through neuroplasticity. The hallucinations fade. The paranoia recedes. The person you love—the one who seemed lost beneath the stranger that methamphetamine created—gradually, sometimes imperceptibly, returns. For families, this timeline requires patience that can feel superhuman. The first six months are particularly brutal, characterized by anhedonia and cognitive fog that make it seem like nothing is working. But beneath the surface, neurons are firing new connections. Receptors are recalibrating their sensitivity. The machinery of consciousness is slowly, steadily rebuilding itself. Your loved one’s psychosis is chemistry, not character. The paranoid accusations, the bizarre beliefs, the emotional volatility—these are symptoms of a dopamine system in crisis, not reflections of who they fundamentally are. This distinction matters because it allows you to separate the person from the behavior, to maintain compassion through impossibly difficult circumstances, to hold onto hope when everything feels hopeless. Professional treatment during the critical first months provides the structure, medical oversight, and psychiatric support that self-managed recovery cannot replicate. Pacific Ridge’s residential approach addresses the full complexity of methamphetamine recovery—the acute detox, the protracted withdrawal, the persistent psychiatric symptoms, and the gradual rebuilding of life skills and relationships. The program isn’t just about preventing relapse; it’s about creating the conditions where neuroplasticity can occur. If you’re reading this in the midst of crisis—if you’re watching someone you love spiral into psychosis, if you’re terrified they’re gone forever—understand that the path forward exists. It’s measured in months rather than days, in small improvements rather than dramatic transformations. But the destination is real, documented in brain scans and cognitive tests and the lived experience of thousands who have walked this road before. The brain heals. Recovery happens. The person beneath the psychosis is still there, and with time and proper care, they can come back.

Ready to Take the Next Step?

Recovery from methamphetamine-induced psychosis is possible. With the right support and treatment, your loved one’s brain can heal.

Or call us directly at 503-558-4638

References:

- Quinones, S. (2021). The New Meth. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/11/the-new-meth/620174/

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2019). Methamphetamine DrugFacts. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/methamphetamine

- Lecomte, T., et al. (2013). Prevalence of non-psychotic psychiatric disorders in methamphetamine users. Mental Health and Substance Use, National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4244888/

- McKetin, R., et al. (2013). The prevalence of psychotic symptoms among methamphetamine users. Addiction, PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23279560/

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2015). Sleep, Sleep Deprivation, and the Brain. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4411904/

- Volkow, N. D., et al. (2001). Loss of Dopamine Transporters in Methamphetamine Abusers Recovers with Protracted Abstinence. Journal of Neuroscience. https://www.jneurosci.org/content/21/23/9414

- Yi, Y., et al. (2018). Risk factors for methamphetamine-associated psychosis. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00689/full

- Amaresha, A. C., & Venkatasubramanian, G. (2012). Expressed Emotion in Schizophrenia: An Overview. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5579299/

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2009). Nutritional Therapies for Mental Disorders. Nutrition Journal. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2738337/

- Oregon Health Authority. (2022). Opioid and Psychostimulant Overdoses in Oregon. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PREVENTIONWELLNESS/SUBSTANCEUSE/OPIOIDS/Pages/index.aspx

Posted in Treatment

Recent Posts

- From Pills to Fentanyl: Understanding the Progression of Opioid Addiction

- Sober Activities in the Willamette Valley: Rediscovering Life Without Substances

- Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS): The Physical Reality of Chronic Marijuana Use

- Protecting Your Career While Seeking Treatment: FMLA and Privacy Rights for Oregon Employees

Are you looking for help?

Pacific Ridge is a residential drug and alcohol treatment facility about an hour from Portland, Oregon, on the outskirts of Salem. We’re here to help individuals and families begin the road to recovery from addiction. Our clients receive quality care without paying the high price of a hospital. Most of our clients come from Oregon and Washington, with many coming from other states as well.

Pacific Ridge is a private alcohol and drug rehab. To be a part of our treatment program, the client must voluntarily agree to cooperate with treatment. Most intakes can be scheduled within 24-48 hours.

Pacific Ridge is a State-licensed detox and residential treatment program for both alcohol and drugs. We provide individualized treatment options, work closely with managed care organizations, and maintain contracts with most insurance companies.

Quick links

Recent Posts

- From Pills to Fentanyl: Understanding the Progression of Opioid Addiction

- Sober Activities in the Willamette Valley: Rediscovering Life Without Substances

- Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS): The Physical Reality of Chronic Marijuana Use

- Meth-Induced Psychosis: Understanding the Brain’s Recovery Timeline

Contact Us

Pacific Ridge- 1587 Pacific Ridge Ln SE

Jefferson, OR 97352 - Email:

[email protected] - Phone:

503-506-0101 - Fax:

503-581-8292

- Copyright © 2026 Pacific Ridge - All Rights Reserved. Web Design & SEO by Lithium

- Follow us on