Call Us For Easy

Confidential Assistance

503-506-0101

It only takes 5 minutes to get started

From Pills to Fentanyl: Understanding the Progression of Opioid Addiction

Posted on: January 1st, 2026 by writer

Table of Contents

- The Medical Origin: When Pain Relief Becomes Dependency

- The Prescription Cliff: Why Patients Turn to the Street

- Fentanyl’s Takeover: Why Two Milligrams Can Kill

- Oregon and Washington: Ground Zero for the Fentanyl Surge

- Case Studies: How Different Roads Lead to the Same Crisis

- Breaking the Cycle: Why Fentanyl Requires 24/7 Medical Supervision

- Final Thoughts

The opioid crisis didn’t begin in back alleys or drug dens. For most people struggling with addiction today, it started in the most trusted place imaginable: a doctor’s office. What begins as legitimate medical care—a prescription for post-surgical pain, a workplace injury, or chronic back problems—can evolve into a life-threatening dependency that families never saw coming.

The opioid epidemic has progressed through three devastating waves. The first wave emerged in the 1990s with the over-prescription of painkillers. The second wave, beginning around 2010, saw a surge in heroin use. Today, we’re living through the third and deadliest wave: synthetic fentanyl, a drug so potent that two milligrams—roughly five grains of salt—can be fatal.

Here’s the sobering reality: nearly 80% of heroin users started with prescription opioids, not recreational drug seeking. At Pacific Ridge, many patients entering treatment began their journey with a dental procedure, sports injury, or chronic pain condition. Their stories aren’t about moral failure or poor choices—they’re about brain chemistry, economic desperation, and a contaminated drug supply that kills indiscriminately.

This article walks you through the physiological, psychological, and economic factors that lead from a prescription bottle to street fentanyl, and why residential treatment is often the only viable path to recovery. Understanding this progression is the first step toward helping someone you love.

The Medical Origin: When Pain Relief Becomes Dependency

The pathway to opioid addiction frequently starts with genuine medical necessity. In 2020, healthcare providers wrote over 142 million opioid prescriptions in the United States—that’s 43.3 prescriptions per 100 people. While prescribing practices have tightened considerably since the height of the crisis, the legacy of widespread opioid use continues to affect millions.

The pharmaceutical industry’s marketing strategies in the late 1990s and early 2000s significantly downplayed the addictive potential of sustained-release opioids. Doctors were assured these medications were safe for long-term pain management. The result? An entire generation of patients was prescribed powerful opioids for conditions that might have been managed with alternative treatments.

How Opioids Rewire the Brain

What makes prescription opioids so dangerous isn’t just their pain-relieving properties—it’s how they fundamentally change brain chemistry. Understanding this biological process is crucial for removing the stigma of “weakness” or “moral failing” from addiction.

When someone takes an opioid medication, the drug binds to mu-opioid receptors in the brain. This binding blocks pain signals and triggers a massive release of dopamine, creating feelings of euphoria and extreme well-being. It’s this dopamine flood that makes opioids so effective for pain relief—and so dangerous.

With continued use, the brain adapts. It reduces the number of functioning opioid receptors in a process called tolerance development. The patient now requires higher doses to achieve the same pain relief they once got from a smaller amount. This isn’t a character flaw—it’s basic neurobiology.

Even more troubling is a phenomenon called Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia (OIH). Long-term opioid use can paradoxically sensitize the nervous system, making patients more sensitive to pain than they were before starting the medication. The very treatment meant to reduce suffering begins causing it, driving patients to take ever-increasing doses just to function normally.

By the time a patient realizes something is wrong, their brain chemistry has already been fundamentally altered. They’re not seeking euphoria anymore—they’re desperately trying to avoid the agonizing symptoms of withdrawal.

The Prescription Cliff: Why Patients Turn to the Street

The transition from prescription pills to street drugs is rarely impulsive. It’s usually a calculated decision driven by desperation, policy changes, and brutal economic reality.

Policy Changes and the Reformulation Crisis

Following legitimate concerns about opioid addiction, the CDC issued prescribing guidelines in 2016 that encouraged healthcare providers to reduce or eliminate opioid prescriptions for chronic pain patients. While well-intentioned, these guidelines created what addiction specialists call the “prescription cliff.”

Patients who had been stable on long-term opioid therapy suddenly found their medications tapered or discontinued entirely. For someone whose brain chemistry has adapted to daily opioid exposure, this isn’t just uncomfortable—it’s unbearable.

The 2010 reformulation of OxyContin compounded the problem. Pharmaceutical companies introduced an abuse-deterrent formulation that made pills harder to crush and snort. While this reduced OxyContin abuse, research from the National Bureau of Economic Research revealed an unintended consequence: substantial substitution toward heroin. When one door closed, desperate patients found another.

The Economics of Desperation

For patients facing the prescription cliff, the math is cruel and simple. On the street, authentic oxycodone costs approximately $1 per milligram. A heavy user requiring 100mg daily faces a $3,000 monthly habit—more than most mortgages.

Meanwhile, a dose of heroin or fentanyl costs $5 to $10.

This isn’t about choosing to use illicit drugs—it’s about economic survival. Patients aren’t chasing euphoria at this stage; they’re avoiding dopesickness, the debilitating withdrawal symptoms that include severe nausea, body aches, insomnia, anxiety, and a feeling that your bones are breaking from the inside out.

The choice becomes painfully clear: spend thousands of dollars you don’t have, suffer through withdrawal that makes you want to crawl out of your skin, or buy cheaper street drugs. It’s not really a choice at all.

Fentanyl’s Takeover: Why Two Milligrams Can Kill

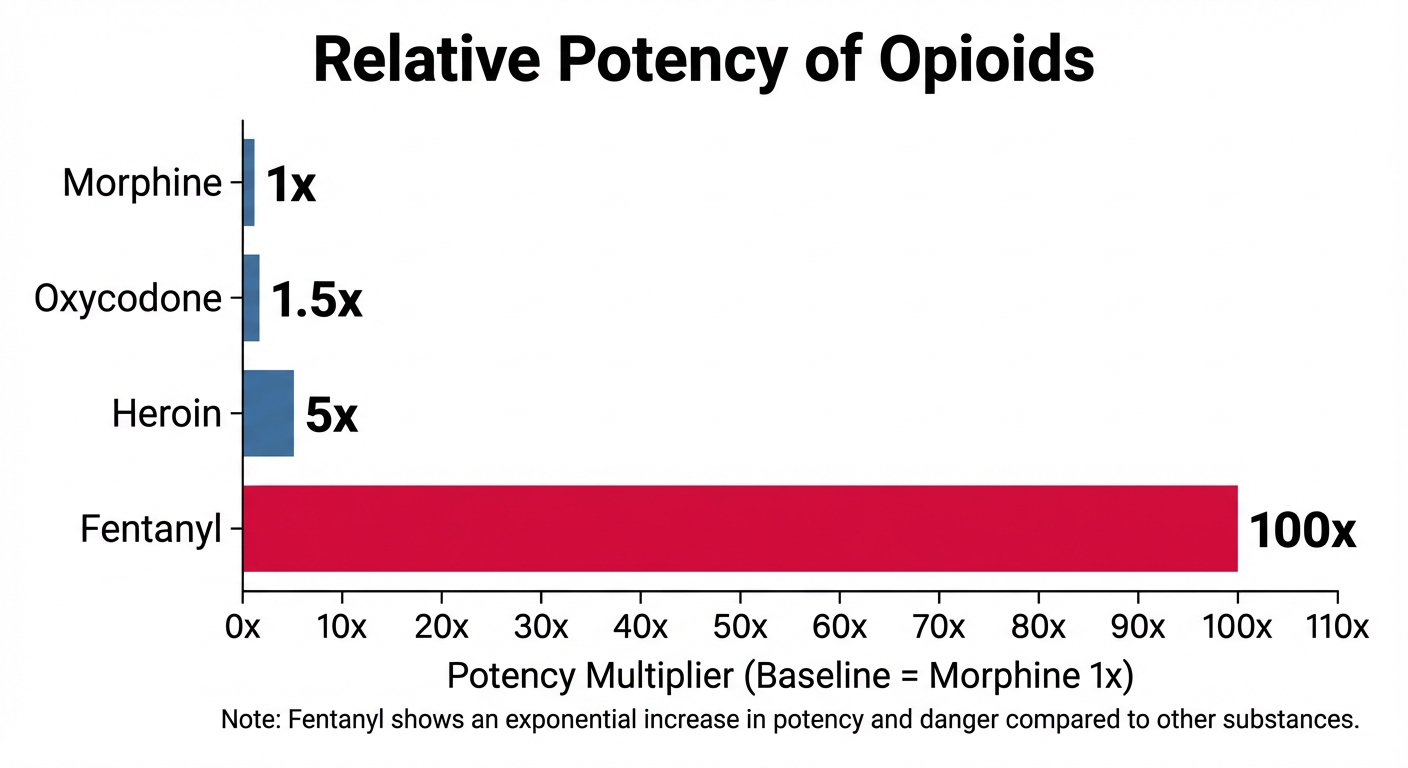

The arrival of synthetic fentanyl has transformed the opioid crisis from a serious public health problem into a genuine mass casualty event. Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that is 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine.

This chart illustrates the exponential danger as users progress from prescription painkillers to synthetic opioids. Notice how fentanyl represents a catastrophic jump in potency—and lethality.

Why Dealers Choose Fentanyl

From a supply chain perspective, fentanyl is a drug dealer’s dream product. Unlike heroin, which requires poppy cultivation and international smuggling operations, fentanyl is synthesized in laboratories. It’s extremely concentrated, meaning smugglers can transport massive quantities in small packages.

For dealers, the profit margins are extraordinary. A tiny amount of fentanyl produces powerful effects, allowing them to stretch their product and maximize profits. For users, this efficiency is deadly.

Two milligrams of fentanyl—an amount equivalent to five grains of table salt—can be a lethal dose for an average-sized adult. There’s virtually no margin for error, and the potency varies wildly from one batch to another.

The Counterfeit Pill Crisis

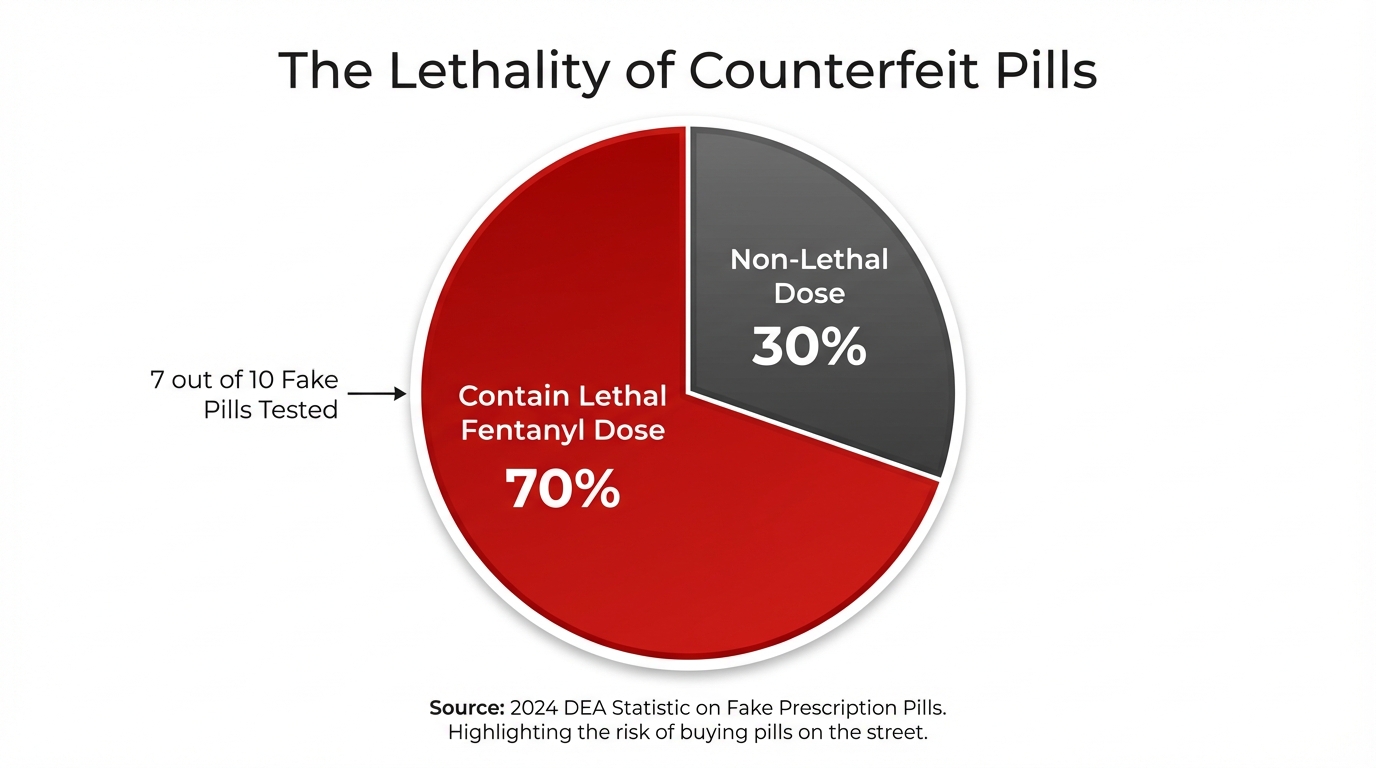

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of the fentanyl crisis is the proliferation of counterfeit pills. Drug traffickers press fentanyl into tablets designed to look exactly like pharmaceutical Percocet, Xanax, or Oxycodone. These pills, often called “Blues” or “M30s” on the street, are virtually indistinguishable from legitimate medications.

The Drug Enforcement Administration reports that 7 out of 10 fake prescription pills seized contain a lethal dose of fentanyl. This means a person who thinks they’re taking a pharmaceutical-grade painkiller may actually be taking Russian roulette in pill form.

The Xylazine Complication

If fentanyl wasn’t dangerous enough, drug traffickers have begun adulterating it with Xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer known on the street as “Tranq.” Xylazine is not an opioid, which means Naloxone (Narcan)—the standard overdose reversal medication—doesn’t counteract its effects.

Xylazine causes severe complications beyond overdose risk. Users develop horrific skin necrosis, with flesh literally rotting away at injection sites. This complication requires extensive medical intervention and sometimes amputation.

The combination of fentanyl and Xylazine creates an overdose scenario that’s harder to reverse and leaves survivors with devastating physical consequences.

Oregon and Washington: Ground Zero for the Fentanyl Surge

The Pacific Northwest, where Pacific Ridge serves its community, has experienced one of the nation’s most dramatic opioid crisis transformations. Historically, the West Coast was primarily a “black tar heroin” market. The arrival of powdered fentanyl changed everything virtually overnight.

Oregon’s Staggering Statistics

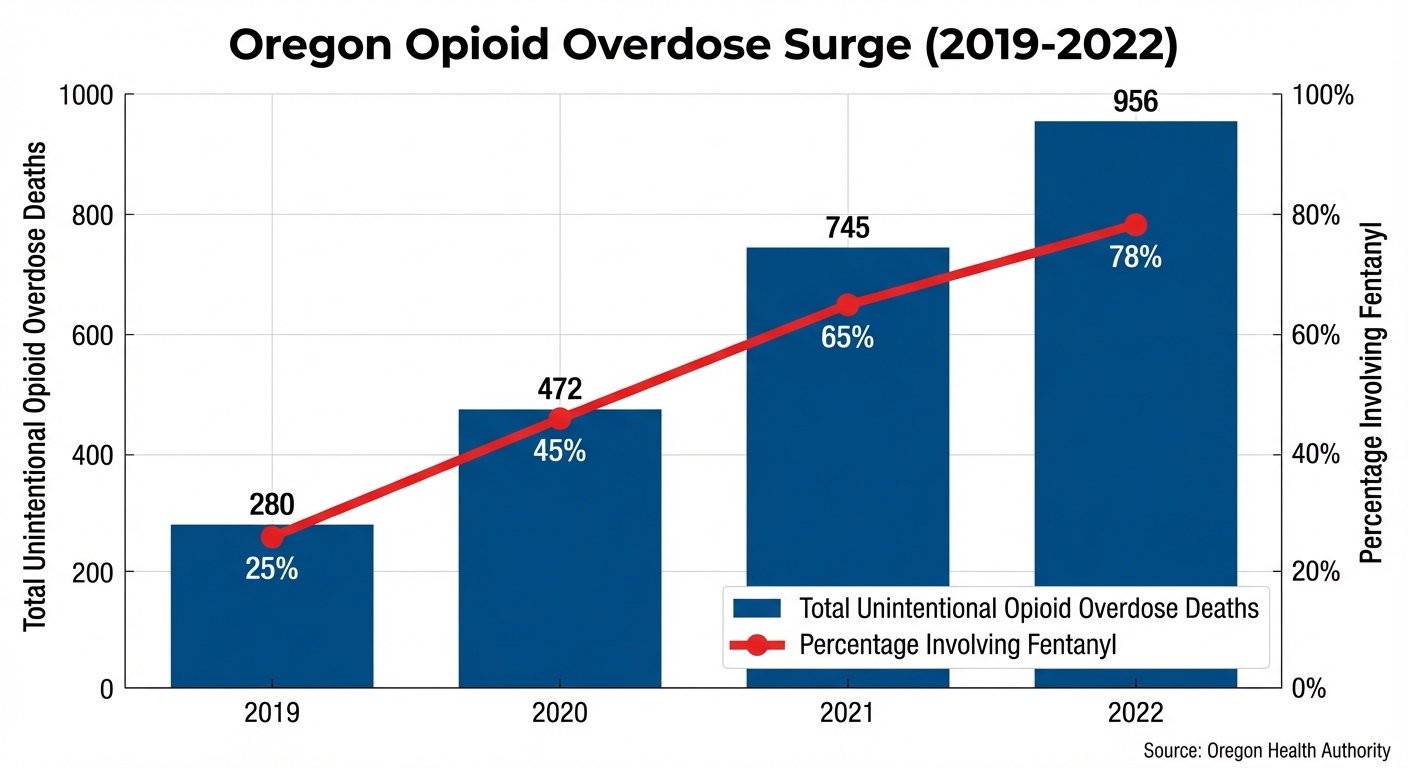

The numbers tell a devastating story. According to the Oregon Health Authority, unintentional opioid overdose deaths involving fentanyl increased by over 600% between 2019 and 2021.

This chart shows both the total overdose deaths and the percentage involving fentanyl. Notice how fentanyl goes from a minority factor in 2019 to dominating nearly 80% of overdose deaths by 2022. This isn’t gradual change—it’s an explosion.

In concrete terms: Oregon went from 280 unintentional opioid overdose deaths in 2019 to 956 in 2022. That’s 956 sons, daughters, parents, siblings, friends, and neighbors lost in a single year.

The Measure 110 Context

Oregon implemented Measure 110 in 2020, decriminalizing possession of user-amount quantities of drugs to emphasize treatment over incarceration. The policy aimed to redirect people from the criminal justice system toward healthcare resources.

While the intention was compassionate, the timing proved catastrophic. The influx of cheap, potent fentanyl overwhelmed Oregon’s treatment infrastructure. Downtown Portland, along with other areas, declared states of emergency as overdoses skyrocketed and public health resources strained to capacity.

This isn’t an argument against treatment-focused approaches—it’s recognition that the fentanyl crisis requires massive investment in residential treatment capacity, not just policy changes.

Case Studies: How Different Roads Lead to the Same Crisis

Behind every statistic is a human story. Understanding the common pathways to fentanyl addiction helps families recognize warning signs before it’s too late.

Mark’s Story: The Occupational Injury

Mark, 45, worked construction his entire adult life. A rotator cuff injury from lifting materials led his doctor to prescribe Percocet for pain management. The medication worked—at first.

After four months, Mark noticed he needed more pills to control the same level of pain. His doctor, following new prescribing guidelines, refused to increase the dose and began tapering Mark’s prescription. Within weeks, Mark was in agony—both from his injury and from withdrawal symptoms.

A coworker offered to sell Mark pills “left over” from his own prescription. Mark started buying pills on the side, spending $60 daily to avoid withdrawal. When his coworker’s supply ran out, Mark faced a choice: suffer through withdrawal or find another source.

Someone introduced him to heroin, which cost $10 for relief that lasted just as long. Mark never wanted to use street drugs. He just wanted his shoulder to stop hurting and the withdrawal symptoms to stop. Today, Mark unknowingly uses fentanyl-laced heroin because that’s what dominates the supply.

Key Insight: Mark’s addiction isn’t driven by euphoria-seeking. It’s driven by pain avoidance and withdrawal management—a crucial distinction that families need to understand.

Sarah’s Story: One Pill, One Mistake

Sarah, 21, was finishing her junior year of college when finals week overwhelmed her. Stressed and exhausted, she accepted a “Blue” from a friend at a party—supposedly an Oxycodone pill to help her relax and get some sleep.

The pill was a counterfeit pressed with fentanyl. Within minutes, Sarah’s breathing slowed dangerously. Her friends found her unresponsive and called 911. Paramedics administered Naloxone, reversing the overdose and saving her life.

Sarah’s story illustrates the “One Pill Can Kill” reality that defines today’s drug supply. There was no addiction history, no progression from prescription to street drugs. One impulsive decision, one fake pill, nearly cost Sarah her life.

These stories share common threads: neither Mark nor Sarah intended to become addicted to opioids. Both encountered a drug supply contaminated with fentanyl. Both needed immediate professional intervention to survive.

Breaking the Cycle: Why Fentanyl Requires 24/7 Medical Supervision

Fentanyl addiction presents unique medical challenges that make outpatient treatment insufficient for most patients. The drug’s properties and the intensity of dependence it creates require specialized residential care.

The Lipophilicity Problem

Fentanyl is lipophilic, meaning it stores in fat cells rather than quickly leaving the system. Unlike heroin, which metabolizes relatively quickly, fentanyl can linger in the body, causing prolonged and unpredictable withdrawal symptoms. Patients experience what clinicians call “stuttering withdrawal”—waves of symptoms that come and go unpredictably.

This extended withdrawal period makes it nearly impossible for patients to successfully detox at home or manage symptoms while trying to maintain normal responsibilities.

The Precipitated Withdrawal Challenge

One of the most significant medical challenges in fentanyl treatment involves timing medication-assisted treatment. Buprenorphine (commonly known as Suboxone) is highly effective for managing opioid addiction, but administering it too early can trigger precipitated withdrawal.

When Buprenorphine is given while fentanyl still occupies brain receptors, it forcibly displaces the remaining drug, sending patients into immediate, severe withdrawal. This precipitated withdrawal is often more intense than natural withdrawal and can be traumatizing enough to drive patients away from treatment entirely.

Proper timing requires careful medical monitoring and expertise—exactly what residential facilities like Pacific Ridge provide. Medical staff can observe patients continuously, assess withdrawal progression, and determine the optimal moment to begin medication-assisted treatment.

What Residential Treatment Provides

Beyond medical stabilization, residential treatment offers several critical elements that outpatient care cannot match:

- Physical Separation from Supply: Removing patients from their environment means separating them from dealers, using associates, and triggering locations. This physical barrier during the vulnerable early recovery period significantly reduces relapse risk.

- Medical Management of Complications: Fentanyl withdrawal causes severe symptoms including dehydration, insomnia, anxiety, and physical discomfort. Medical staff can manage these symptoms with appropriate medications and interventions, making the process safer and more bearable.

- Psychological Reconstruction: Many patients carry profound shame about their progression from prescription patient to street drug user. Residential treatment provides intensive therapy to address this guilt, rebuild self-worth, and develop coping mechanisms for life after treatment.

- Structured Environment: Early recovery requires learning new patterns and skills. Residential treatment provides structure, accountability, and practice in healthy routines before patients return to environments filled with triggers.

The Bottom Line: The intensity of fentanyl dependence, combined with the lethality of the contaminated drug supply, makes residential treatment not a “last resort” but often the most effective first step toward lasting recovery.

Final Thoughts

The journey from a legitimate prescription bottle to fentanyl addiction represents a tragic convergence of biological vulnerability, policy failures, and predatory drug trafficking. This progression isn’t about moral weakness—it’s about brain chemistry that’s been hijacked, economic desperation, and a drug supply that has become exponentially more dangerous.

Understanding this progression transforms how we view addiction. The person struggling with opioid dependence likely started with a genuine medical need. Their brain adapted to the medication through normal physiological processes. Economic pressure or prescription restrictions pushed them toward alternatives they never intended to use. And now they’re trapped by both the fear of withdrawal and the genuine danger of every dose.

For families watching this unfold, the most important insight is this: your loved one is probably not chasing euphoria anymore. They’re avoiding the physical agony of withdrawal and trying to manage pain—both physical and psychological. The shame they feel about their situation often prevents them from asking for help.

The fentanyl crisis has made waiting for “rock bottom” a potentially fatal strategy. Two milligrams—five grains of salt—can be lethal. Seven out of ten counterfeit pills contain potentially fatal doses. Every use could be the last.

Professional intervention through residential treatment offers the safest path to recovery. With medical supervision, psychological support, and structured care, people can successfully navigate fentanyl withdrawal and begin rebuilding their lives.

If you or someone you love is struggling with opioid addiction, reaching out is not admitting defeat—it’s choosing survival. Pacific Ridge provides confidential assessments and evidence-based treatment specifically designed for opioid dependency. Recovery is possible, but it requires professional help.

The opioid crisis evolved from prescription bottles to street fentanyl. The path back from addiction requires understanding, compassion, and expert medical care. Don’t wait for a tragedy that could have been prevented.

Ready to Take the First Step Toward Recovery?

For confidential help and information about treatment options, contact Pacific Ridge today. Recovery is possible, and every day matters.

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021). Understanding the Epidemic. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2018). Prescription opioid use is a risk factor for heroin use. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/prescription-opioids-heroin/prescription-opioid-use-risk-factor-heroin-use

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2021). U.S. Opioid Dispensing Rate Maps. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/rxrate-maps/index.html

- Lee, M., et al. (2011). A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician Journal. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21412369/

- Alpert, A., Powell, D., & Pacula, R. L. (2018). Supply-Side Drug Policy in the Presence of Substitutes: Evidence from the Introduction of Abuse-Deterrent Opioids. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w23031

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2022). World Drug Report 2022: Market Dynamics. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2022.html

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). (2023). Fentanyl Awareness. https://www.dea.gov/factsheets/fentanyl

- United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). (2024). One Pill Can Kill: Fake Pills Fact Sheet. https://www.dea.gov/onepill

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). What You Should Know About Xylazine. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/other-drugs/xylazine/faq.html

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). (2021). Opioid Potency and Pharmacology. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553166/

- Oregon Health Authority (OHA). (2023). Opioid Overdose Data Dashboard. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PREVENTIONWELLNESS/SUBSTANCEUSE/OPIOIDS/Pages/data.aspx

- Oregon Public Broadcasting (OPB). (2024). Governor Kotek, Multnomah County, Portland declare fentanyl state of emergency. https://www.opb.org/article/2024/01/30/oregon-governor-tina-kotek-multnomah-county-portland-fentanyl-state-of-emergency/

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2021). TIP 63: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/TIP-63-Medications-for-Opioid-Use-Disorder/PEP21-02-01-002

Posted in Treatment

Recent Posts

- From Pills to Fentanyl: Understanding the Progression of Opioid Addiction

- Sober Activities in the Willamette Valley: Rediscovering Life Without Substances

- Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS): The Physical Reality of Chronic Marijuana Use

- Protecting Your Career While Seeking Treatment: FMLA and Privacy Rights for Oregon Employees

Are you looking for help?

Pacific Ridge is a residential drug and alcohol treatment facility about an hour from Portland, Oregon, on the outskirts of Salem. We’re here to help individuals and families begin the road to recovery from addiction. Our clients receive quality care without paying the high price of a hospital. Most of our clients come from Oregon and Washington, with many coming from other states as well.

Pacific Ridge is a private alcohol and drug rehab. To be a part of our treatment program, the client must voluntarily agree to cooperate with treatment. Most intakes can be scheduled within 24-48 hours.

Pacific Ridge is a State-licensed detox and residential treatment program for both alcohol and drugs. We provide individualized treatment options, work closely with managed care organizations, and maintain contracts with most insurance companies.

Quick links

Recent Posts

- From Pills to Fentanyl: Understanding the Progression of Opioid Addiction

- Sober Activities in the Willamette Valley: Rediscovering Life Without Substances

- Cannabis Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS): The Physical Reality of Chronic Marijuana Use

- Meth-Induced Psychosis: Understanding the Brain’s Recovery Timeline

Contact Us

Pacific Ridge- 1587 Pacific Ridge Ln SE

Jefferson, OR 97352 - Email:

[email protected] - Phone:

503-506-0101 - Fax:

503-581-8292

- Copyright © 2026 Pacific Ridge - All Rights Reserved. Web Design & SEO by Lithium

- Follow us on